The horseshoe-shaped street configuration of New Plymouth, Idaho, often arouses the passing curiosity of first-time visitors. Those that look into its history learn that the town began as a utopian farm community founded in 1894 as a result of promotional efforts by William E. Smythe, a Midwestern journalist and crusader for the "conquest of arid America" by means of irrigation.

Irrigating the arid West had been the dream of progressive developers ever since the Powell survey of the 1880s. John Wesley Powell, Director of the U.S. Geological Survey, after months in the field studying watersheds, river systems, soils and dam sites, identified the most suitable areas west of the 100th meridian for irrigated agriculture. He wanted the government to stop speculators from grabbing the best lands before they could be systematically developed and equitably distributed.

A decade earlier, social critic Henry George’s solution to inequality and land monopolization was to tax the profits from rising land values. But George’s brand of socialism had little appeal to the rising urban middle class in late 19th-century America. Neither did Powell’s ecological emphasis. Though his science was sound, his attack on privatization upset powerful business interests and their representatives in Congress. For over a decade they fought and won numerous battles over federal control of western lands, leaving the West vulnerable to exploitation by free-wheeling entrepreneurs and speculators.1

When it came to public land acquisition, changes in federal and state land laws since the 1840s helped equalize the rural class structure by putting farmer-settlers on a par with wealthy speculators. Regardless of connections or status, by the 1880s anyone could preempt land in advance of survey, take a homestead, buy land with cash or a loan on easy terms, or get a land grant for promising to reclaim swampland, plant trees or irrigate. Although they made public lands easy to acquire, most of these laws did not match the environmental conditions where they were applied.

Arid lands needed water to grow crops; large cattle herds needed much more grazing land than the maximum allowed individuals under various land laws. The incongruities between unrealistic expectations and actual practice left a wide opening for fraud.2

When it came to public land acquisition, changes in federal and state land laws since the 1840s helped equalize the rural class structure by putting farmer-settlers on a par with wealthy speculators. Regardless of connections or status, by the 1880s anyone could preempt land in advance of survey, take a homestead, buy land with cash or a loan on easy terms, or get a land grant for promising to reclaim swampland, plant trees or irrigate. Although they made public lands easy to acquire, most of these laws did not match the environmental conditions where they were applied.

Arid lands needed water to grow crops; large cattle herds needed much more grazing land than the maximum allowed individuals under various land laws. The incongruities between unrealistic expectations and actual practice left a wide opening for fraud.2

Manipulating poorly designed legislation to make it workable seemed the only answer to many westerners and their representatives at every level of government. For example, the Desert Land Act, though designed for large-scale cattle interests, enabled canal companies to privatize large tracts of the public domain. Idaho Territorial Governor E.A. Stevenson in 1884 praised the act for helping convert the Snake River Valley from an "arid, parched, and unsightly desert" into "rich and blooming agricultural lands." His optimism was premature.

Some companies started with high expectations but folded because of poorly designed canals that cost too much to maintain or failed to deliver an adequate water supply. Others bogged down over title fights and other legal problems. Bankruptcy was often the result, which dried up investment capital and delayed further development.3

Smythe stepped into the breach a decade later on behalf of the small farmer. In the 1890s democratic values seemed threatened by the consequences of industrialization. Populists and progressives warned of an ever-widening gap between rich and poor that undermined the "promise of American life." With the frontier "closed" because of rising population rates per square mile, small farmers could no longer look west for new opportunities. That was an ominous sign, wrote Frederick Jackson Turner, who believed American democracy owed its distinctive character to cheap land and westward expansion.

But Smythe believed the American dream could be extended through reclamation. Arid America, he said—meaning tillable soil west of the 100th meridian where rainfall was insufficient for traditional agriculture--held new promise for small farmers.4

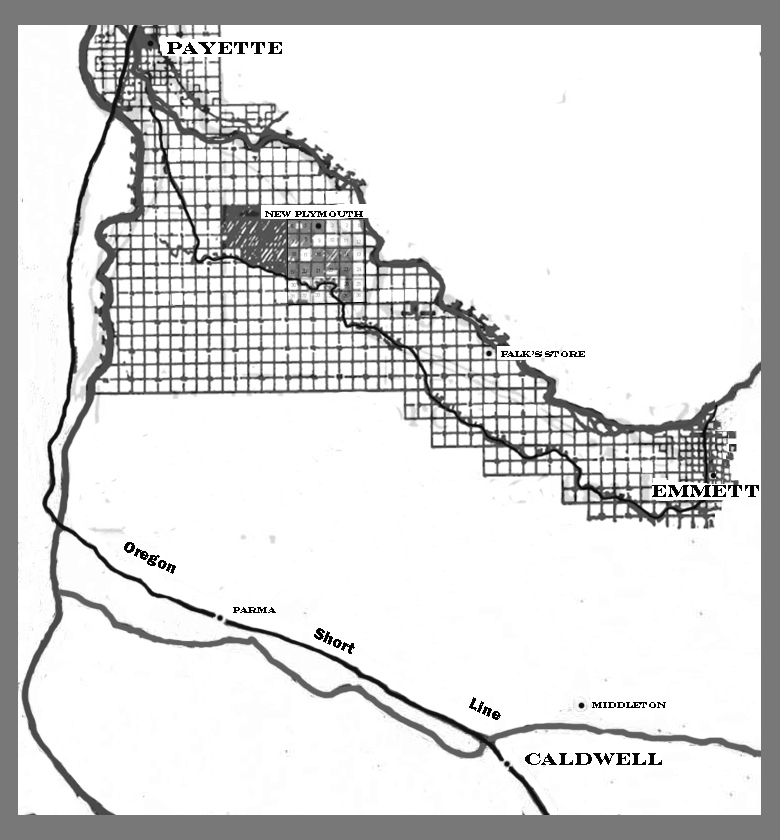

The focus of Smythe’s Idaho crusade highlighted land that once had been dismissed as "desert" by farmers following the Oregon Trail to the verdant Willamette Valley. By the 1880s, as coastal lands rose in value and inland population centers grew, developers saw new potential among the sagebrush plains and valleys of Southwest Idaho. Thanks to promotional pamphlets and newspaper articles, the lower Payette Valley's agricultural potential was well-advertized.

Instead of a "barren" and "foreboding" land that early travelers dismissed on their way to Oregon, promoters of this 120-square mile area bounded by the Payette and Snake rivers to the north and west, hilly uplands to the south, and high bluffs above Emmett to the east, wrote dreamy descriptions of a small-farm paradise, with loamy bottomlands and sandy terraces ideal for raising fruits and vegetables. One observer on Freezeout Hill above Emmett in 1892 looked 30 miles northwest toward Payette. Ignoring the sagebrush below he envisioned "one continuous picture of gleaming river, green fields, and level virgin soil, bounded on either side by the everlasting hills...."5

Payette Valley had three essential geographic conditions for the development of commercial agriculture: a long harvest season, rich and varied soils, and a good water supply. Thanks to the Union Pacific Railroad, it also had an adequate transportation system that would get better as the Valley's economy expanded and diversified.

Railroads came late to southern Idaho, and without the competition stirred by transcontinental rivalry they may have been delayed even longer. For a decade after driving the last spike at Promontory Point, UP officials had wanted to expand. They saw themselves at a dead end unless they built spur lines to tap the revenue potential of the Pacific Northwest. By the late 1860s competing railroads were already building toward the timber, mines, and farmlands of the region. Before the UP could add another line, however, a decade of national economic uncertainty brought most railroad construction to a halt.6

Not until the late 1870s did business pick up enough to revitalize railroad development in the Pacific Northwest. In 1878 UP officials started construction of a narrow gauge line northward from Salt Lake to tap the lucrative mining traffic in Montana. The reorganized Utah and Northern took three years to complete. While UP crews were still laying track to Butte, a new opportunity opened to build another UP subsidiary, the first railroad across southern Idaho. Its success depended on the ambitions of Henry Villard, a German-American financier and railroad promoter. In 1879 he organized the Oregon Railway & Navigation company and planned to build eastward to Umatilla along the southern bank of the Columbia River. Feeder lines extending in all directions would catch regional traffic and divert it from the proposed route of the Northern Pacific railroad, his main rival north and east of the Columbia.7

Joining Villard's rails to a UP branch line through the sagebrush plains along the Snake River was the inevitable next step. The Oregon Short Line, so named by UP President Sidney Dillon, started in western Wyoming in 1881 and ended nearly 400 miles and three years later just across the Idaho border. It skirted the southern and western edges of Payette Valley, passed through Caldwell and Parma, and then crossed the Snake River to Nyssa and Ontario Oregon before returning to Idaho at Payette on its way north. Connecting it with Villard's regional system at Huntington Oregon made Portland the leading transcontinental hub in the Pacific Northwest--at least until Seattle grew enough to take over that title in the 20th century.8

News of the conjunction at Huntington raised the hopes and dreams of long-suffering Idaho residents. Their chronic isolation from the outside world seemed about to end. But the news also stirred the financial dreams of land speculators and town site developers. UP officials had another audience in mind: small farmers and their families. They were encouraged to settle on sagebrush lands and build communities that needed the services that only good rail service could provide. In railroad jargon, this was "way traffic," a vital component of profitability. To stimulate that traffic, Jay Gould, UP's cynical CEO, hired a publicity agent, Robert Strahorn, a former Colorado journalist and promoter of what he termed the "New West." He spent eight years writing guidebooks and pamphlets advertizing the resources and attractions of the Pacific Northwest.9

Perhaps unwittingly, UP officials also stoked the fires of speculation by organizing a subsidiary, the Idaho and Oregon Land Improvement Company, to lay out town sites along the proposed route and reserve railroad station land. After the required maps were filed with the General Land Office detailing the exact route across Idaho, speculators knew precisely where to put their money. Federal legislation in 1875 had protected the railroad right of way through public lands not otherwise reserved, but no law prevented speculators from encumbering land that seemed certain to increase in value after the road was built.10

Land transactions in the lower Payette Valley during its formative years show the effects of speculation Inflated land prices in the Populist era brought loud complaints from small farmers and their advocates. In 1893, the Caldwell Tribune blamed speculators for slowing development in Payette Valley by jacking up land prices "out of all proportion to present values." W.E. Smythe's remedy was to organize an irrigation crusade on behalf of small farmers, but launching New Plymouth Colony actually did more to inflate local land values than building the Oregon Short Line. The Union Pacific in Idaho had little or no land to sell. Indeed, it did not complete a spur to New Plymouth until 1910, and had to buy land to build it.

Most Payette Valley landowners were farmer-settlers who acquired property directly from the General Land Office. (See Chart Below: Payette Valley Land Privatization: from General Land Office to Individuals, and Resales 1886-1901, Compiled by Ron Limbaugh)

Prices for virgin land were very low before 1890, thanks to free lands acquired through homestead filings and the Desert Land Act. The average cost per acre was less than one cent in the township where New Plymouth later stood. Between 1890 and 1894, as privatized land was resold, the average price rose to $2.39. By 1900 land prices reached $5.90, more than doubling in the first five years of New Plymouth Colony.11

The terms "speculator" and "settler" are often found in western literature, but they are not necessarily opposites. Speculators normally are distinguished by their absence from the land they own. They may be eastern or foreign investors in a land or insurance corporation, with agents who buy and sell property for a profit; or merchants, bankers or other businessmen living in rural towns and investing directly in local lands. But as Ray Allen Billington and other historians of the westward movement have noted, a speculator could also be a small farmer with more land than he can use. He may want to sell the excess, turn it over to his children, or use it later himself. Regardless of motives for holding excess lands, farmer-settlers usually enjoyed the respect of their peers on the western frontier. Those who lived on the land did not suffer the class distinctions and anti-capitalist social stigmas often associated with absentee ownership.12

Both kinds of speculators appeared early in Payette Valley. The most successful were pioneer developers in and around the town of Payette. Thirty years before New Plymouth was founded, a community at the juncture of the Payette River and the Snake started as a way station for pack trains and miners traveling from Walla Walla to the Boise Basin mines. Some of these early travelers found they could make more money as farmers and ranchers. Settling on preempted land along the river, they raised hay and produce for the mines and trade centers farther inland. William Stuart, for example, was one of the Valley's earliest settlers, arriving in 1864 from Missouri with his wife after crossing the plains in a covered wagon. An Irish native, he preempted land near Falk's store and for the first few years earned a good living selling hay, beef and vegetables to miners and merchants.

At his death in 1895 he was one of Idaho's largest landowners, with 3160 acres in Payette Valley acquired through a combination of preemption, homestead, direct purchase, and the Desert Land Act. His son W.E. Stuart carried on his father's ranching operations, but shrewdly anticipated the profits to be made from rising land values. Land he bought from the General Land Office for $1.25 per acre in 1893-94, he sold in 1896 for $7.50.13

Both kinds of speculators appeared early in Payette Valley. The most successful were pioneer developers in and around the town of Payette. Thirty years before New Plymouth was founded, a community at the juncture of the Payette River and the Snake started as a way station for pack trains and miners traveling from Walla Walla to the Boise Basin mines. Some of these early travelers found they could make more money as farmers and ranchers. Settling on preempted land along the river, they raised hay and produce for the mines and trade centers farther inland. William Stuart, for example, was one of the Valley's earliest settlers, arriving in 1864 from Missouri with his wife after crossing the plains in a covered wagon. An Irish native, he preempted land near Falk's store and for the first few years earned a good living selling hay, beef and vegetables to miners and merchants.

At his death in 1895 he was one of Idaho's largest landowners, with 3160 acres in Payette Valley acquired through a combination of preemption, homestead, direct purchase, and the Desert Land Act. His son W.E. Stuart carried on his father's ranching operations, but shrewdly anticipated the profits to be made from rising land values. Land he bought from the General Land Office for $1.25 per acre in 1893-94, he sold in 1896 for $7.50.13

By the 1870s cattlemen and farmers were competing with each other for water and land in Payette Valley. As farms and orchards sprouted among the fertile bottomlands and gentle slopes of the lower valley, however, the cattle industry gradually gave way to apples and prunes, two of the most successful orchard crops. By the mid-1880s Canyon County, Payette's jurisdictional home before 1915, was shipping thousands of pounds of fresh fruit on the Oregon Short Line to urban markets throughout the Pacific Northwest and eastward.14

Robert Kennedy's experience in lower Payette Valley exemplifies this evolution from cattle to fruit culture. An Irish immigrant like Stuart, he took up a homestead along the Payette River in 1885, bought an additional 160 acres for $200 in 1888, and then used the Timber Culture Act in 1895 to file on 80 acres adjacent to his holdings. The filing fee was $6. Unlike many fraudulent TCA applicants who relinquished their claim to an agent for a cash kickback, Kennedy planted apples after clearing the sagebrush and held on until the land was patented 10 years later. His other cash investment paid off handsomely during the New Plymouth boom in 1896, when he sold 240 acres to Frank M. Lewis for $2000. Apparently he had second thoughts, however; four months later Kennedy bought back 250 acres for the same price from the same man. Kennedy's private cemetery amid the apple trees was the first in the township, just two miles east of the Catholic church.

Payette's growing reputation as a center for fruit culture opened new opportunities for entrepreneurs. One of the most successful early businessmen was Albert B. Moss, one of Payette's founders. Arriving in 1881 from Illinois, he and his brother Frank built a lumber business selling ties to the Oregon Short Line. After expanding successfully into retail merchandizing and banking, they used the same federal land laws as farmers and ranchers to privatize public lands that could easily be subdivided and sold. By 1895, for a combined investment of $150, the brothers had accumulated some 1200 acres in two townships just south of Payette. They sold 40% of their holdings the same year to the Payette Valley Irrigation and Water Power Company (PVIWP) for $9,600.15

The Moss brothers were part of a group of advisors and agents working with W.E. Smythe to tie up key properties around his chosen townsite in lower Payette Valley before outside speculators could grab them. Before the mid-'90s, Smythe had condemned the fraudulent use of the Desert Land Act by canal companies and other corporate interests. He demanded changes in federal land laws, but when that campaign fizzled he turned to colonization as the best hope for the small farmer. Using the same law he had earlier attacked, Smythe contracted with land agents to file on 5,000 acres to be reserved for colonists in 20-acre parcels at $10 per acre. The price included a water right and the cost of infrastructure. For $3 more per acre purchasers could buy land cleared of sagebrush.16

Smythe did not name the "large number of individuals" who acquired land for Plymouth colony, but Benjamin P. Shawhan and his family were probably the most important. Shawhan was a Midwesterner with plenty of experience in the financial world. In Iowa he and his father had developed a profitable banking business after years in the retail trade. By the late 1880s he had moved to New York to become secretary-treasurer of a major Wall Street financial firm. The Equitable Mortgage company had grown rapidly under the free-wheeling financial system of the day. Using real estate mortgages it bought from Midwestern lenders as collateral, Equitable attracted European creditors by issuing bonds with a guaranteed interest rate. All went well until the Panic of 1893 and the national depression that followed. Equitable folded, and the New York Security & Trust Company picked up the pieces.17

A year before the Equitable crash Shawhan resigned "for his health." He came to Payette in 1892--far from the eastern storm center--to pursue a new career as town promoter and real estate speculator. Why Payette? Sometime in the early planning stages for New Plymouth colony, Smythe toured the area and quietly organized an advisory committee made up of businessmen and promoters from Idaho and several other western states. Shawhan may not have met Smythe personally before the early 1890s, but the two were natural allies. Both promoted Payette Valley development, but Shawhan's practical banking and mercantile experience complemented and strengthened Smythe's utopian call for a "Republic of Irrigation."18

Between 1894 and 1895 the Shawhans collectively filed on 640 acres in Payette Valley using DLA provisions. They bought another 600 acres on the resale market.

The details of these transactions are vague, but colony organizers apparently arranged with their agents to sell directly to colonists. (See Chart Below: NEW PLYMOUTH COLONY LANDS AND PURCHASERS, 1896, Compiled by Ron Limbaugh)

New Plymouth Colony (NPC) also sold land after it was incorporated, as did PVIWP, the latter in effect a subsidiary of NPC. Corporate sales represented only 62% of the DLA land taken up by colonists before 1900; the rest came from private landowners like the Shawhans. They collected $13,910 for 1,225 acres within New Plymouth township by 1898, amounting to a 48% return on their investment over a four-year period.

Between 1894 and 1895 the Shawhans collectively filed on 640 acres in Payette Valley using DLA provisions. They bought another 600 acres on the resale market.

The details of these transactions are vague, but colony organizers apparently arranged with their agents to sell directly to colonists. (See Chart Below: NEW PLYMOUTH COLONY LANDS AND PURCHASERS, 1896, Compiled by Ron Limbaugh)

New Plymouth Colony (NPC) also sold land after it was incorporated, as did PVIWP, the latter in effect a subsidiary of NPC. Corporate sales represented only 62% of the DLA land taken up by colonists before 1900; the rest came from private landowners like the Shawhans. They collected $13,910 for 1,225 acres within New Plymouth township by 1898, amounting to a 48% return on their investment over a four-year period.

Other DLA land agents for the colony did much better. The Moss brothers sold 520 of their 1147 acres for a gross gain of $10,291 on land that cost them virtually nothing to acquire. Daniel Wertman, a Democrat from Pennsylvania who moved to Payette in the early 1890s, held a 640-acre DLA grant along the river just north of the New Plymouth townsite. In March 1895, the same month Smythe's "infomercial" on the new colony hit the newsstands, Wertman filed for a homestead in the townsite itself but soon commuted the claim. He bought the 162-tract for $202.50 in cash. Land reformers wanted the homestead commutation clause repealed, but congressmen from states with extensive homestead filings objected. Commutation allowed settlers to obtain titles within months after filing, and titles were necessary to obtain development loans. State and local governments, solely dependent on property taxes for revenue, also opposed any reforms that would delay the privatization of public lands. Nine months after his purchase, Wertman sold 85% of his commuted acreage in small parcels for an average of $18 per acre, nearly a 1000% return on his investment.19

Wertman, the Moss brothers, and the Shawhans were not typical small farmers, but at least they lived and worked where they invested. By the social norms of the day, they made money and gained stature at the same time as successful settler-speculators. Most of Smythe's land agents fit the same category, but at least two were absentee owners who filed DLA claims on acreage they most likely never visited in person. James V. Parker and his wife Louisa were Vermont natives, born close to each other in the 1840s. James traveled west during his career as a railroad clerk, but later moved to Marietta Ohio on the Ohio River. Sometime before Smythe's irrigation campaign went public and after the Payette Valley water company organized, the Parkers made a deal. The details are unknown, but the intent to use DLA provisions to secure land for PVIWP was evident in 1894. Every DLA applicant had to declare under oath that the claim was "not made for the purpose of fraudulently obtaining title to mineral land, timber land, or agricultural land."

Lacking men and means to enforce such rules, no one paid much attention to them. The Parkers filed separate DLA claims for a total of 920 acres in New Plymouth township. That same year PVIWP paid nearly $21 an acre for 240 acres of Parker land--$3 per acre higher than the average of all DLA land transactions in the area. The Parkers sold another 200 acres in 1895 to a relative for a slight discount: $17.50 per acre. With no investment or overhead, in one year they had cleared $8500 and still had 480 acres to sell.20

While Smythe’s land agents were at work, the Payette Valley Irrigation and Water Power Company struggled to survive the financial upheavals of the 1890s. Like most private canal companies in the arid West, PVIWP had more ambitions than revenue. Organized by a Denver development company in the late 1880s, it borrowed $400,000 from Wall Street to dig a ditch five feet deep and 25 feet wide that meandered 40 miles from the Payette River at Emmett through the sagebrush terraces of the lower valley. Before 1894, at least, no evidence has surfaced tying Smythe directly to PVIWP, but indirectly his call for revitalizing small-farm democracy through irrigation helped motivate utopian planners and canal investors alike.21

The Panic of 1893 and the depression that followed ruined many undercapitalized companies like PVIWP. Construction stopped when the company couldn't pay its bills or service its debt. It declared bankruptcy in 1894, and its remaining assets fell into the hands of receivers from the New York Security and Trust Company--the same firm that had handled the Equitable failure. For the next three years the trustees allowed construction to continue but kept a tight lid on expenses, The result was a poorly-managed and maintained canal system that satisfied neither users nor bondholders.

The situation was ripe for a white knight--a venture capitalist that could negotiate a settlement to put the canal company back on its feet, with proper financing and efficient management. B.P. Shawhan had the right credentials, but was too busy managing his other Payette Valley businesses to do much more than assume the role of President of the bankrupt company. Shawhan had another candidate in mind, Clarence E. Brainard, a Utah real estate agent and canal promoter. Though 10 years older than Shawhan, both were from Keokuk County, Iowa, where Shawhan's father had been a Civil War recruiter and later a farm equipment dealer before coming to Payette. During Smythe's promotional tour through Utah Brainard had met the irrigation crusader and helped him promote the New Plymouth project. Though he lived and worked in Ogden, he became deeply involved in organizing the New Plymouth Colony project as one of its founding directors and the largest shareholder.22

Acting on behalf of PVIWP's shareholders and long-suffering water users, Brainard went to New York in 1897 to negotiate a deal with the receivers. Rather than seek refinancing through the trust company, however, he returned to Payette with an offer to buy up the land holdings of the defunct canal company himself, provided local farmers bought the canal. Agrarian cooperative purchasing and marketing experiments received considerable support among small farmers in the Midwest in the 1880s and '90s. Populists promoted them as a way to fight the power of corporate oligopolies, but many of them died along with the Populist Party after 1896. Brainard's proposal was locally popular, but impractical so long as the national economy was still in depression. Payette Valley farmers lacked the resources and leverage to secure enough investment capital to take up the offer until the financial crisis was over. Not until 1901 were stockholders of New Plymouth Colony able to raise enough capital to settle with the receivers and take control of the canal. They borrowed another $60,000 to reorganize the old PVIWP as the Farmers Cooperative Irrigation Ditch Co., with Brainard holding most of the stock in the formative years.23

Acting on behalf of PVIWP's shareholders and long-suffering water users, Brainard went to New York in 1897 to negotiate a deal with the receivers. Rather than seek refinancing through the trust company, however, he returned to Payette with an offer to buy up the land holdings of the defunct canal company himself, provided local farmers bought the canal. Agrarian cooperative purchasing and marketing experiments received considerable support among small farmers in the Midwest in the 1880s and '90s. Populists promoted them as a way to fight the power of corporate oligopolies, but many of them died along with the Populist Party after 1896. Brainard's proposal was locally popular, but impractical so long as the national economy was still in depression. Payette Valley farmers lacked the resources and leverage to secure enough investment capital to take up the offer until the financial crisis was over. Not until 1901 were stockholders of New Plymouth Colony able to raise enough capital to settle with the receivers and take control of the canal. They borrowed another $60,000 to reorganize the old PVIWP as the Farmers Cooperative Irrigation Ditch Co., with Brainard holding most of the stock in the formative years.23

With canal development well underway and the designated settlement lands safe from outside speculators, Smythe's agrarian experiment in Payette Valley moved from planning to promotion. In April 1894, during the third National Irrigation Congress in Chicago, Smythe gathered a small group of followers together to discuss how to implement the project. They agreed to charter a joint-stock company that would lead colonists to the promised land. The idea of a new pilgrimage caught the imagination of Edward Everett Hale, famous for his New England stories and sermons. He said the company should be called New Plymouth, "a name sacred to liberty in the annals of Anglo-Saxon men." Two weeks later, a delegation of designated trustees took the train to Payette to get a first-hand look at the proposed location. Since the land was already encumbered, there was no need for secrecy. After two weeks touring the area, talking with land agents, local farmers, and fact-checking the preliminary information, the delegates returned with an enthusiastic endorsement. Doubtless Smythe expected no less. With everything in place except formal incorporation, he prepared the first public announcement.

It appeared in the March 1895 issue of Irrigation Age, and later in an illustrated brochure describing the colony's functions and goals.24

Smythe "proposed" to make New Plymouth his own home, but several California projects distracted him over the next few years and he never revisited his Idaho experiment. It was left in the hands of local leaders, especially B.P. Shawhan and C.E.Brainard. In 1896 Brainard and five directors from Ogden, Boise and Payette incorporated the New Plymouth Land & Colonization Company (NPC). Promoters attracted colonists mainly from the ranks of Midwestern small farmers, but growth was slow because of the lingering depression and the availability of adjacent land at prices ranging from $2.50 to $100 per acre. By 1900 in New Plymouth township only a few immigrants had followed the colony prescription. They bought company stock in minimum blocks of $200, which entitled each shareholder to 20 acres of tillable land and a one-acre town plot. Inspired by Puritan tradition, town planners designed New Plymouth as a horseshoe-shaped residential village and market center, where farmers and their families were to live when not working the surrounding fields and orchards. Though politically secular and socially democratic, culturally it mirrored the values of its Anglo-American Protestant majority.25

Although critics of utopian communities labeled them "socialism" or worse, Smythe's colony in Idaho was too decentralized and too loosely structured to be much more than a brief secular experiment in community cooperation. Despite the early promises, it didn't work very well in practice. Cooperative farming and living quickly gave way to a more traditional pattern of agricultural development. Payette Valley grew as the national economy picked up after 1896. With productive soil, good weather, cheap and abundant irrigation water, railroad access at Payette and favorable market conditions, New Plymouth's small farmers entered a "golden age of agriculture" that lasted through World War I.